Liberalising foreign investment norms and encouraging inflow of FDI have been some of the key focal points of the Indian Government's economic policy for the past decade. For over six fiscal years, India has seen a steady increase in FDI inflows, interrupted for the first time in the first financial quarter of 2019. In September 2019, India diluted FDI restrictions across sectors such as single-brand retail trading, commercial coal mining and contract manufacturing. This increasing focus on foreign investment is, however, situated in the backdrop of India's reluctance towards committing to international treaties guaranteeing investor and investment protection.

Since the 2011 Investment Arbitration award in favour of White Industries against India, there have been multiple arbitration claims filed against India by foreign investors. India has reacted to these claims by serving notices of termination under a majority of its BITs and has released a Model BIT in 2016, which expands regulatory space and limits investor protection. This article provides insights into India's policy on foreign investment, contextualises, and contrasts the dichotomy between a highly liberalised FDI regime and an overly cautious approach towards investment treaty protection. The article highlights the various contemporary issues in India's foreign investment laws, identifies the relationship between BITs and FDI inflow, and traces, through case law, the rationale behind India's current position on BITs.

Take home

For over six fiscal years, India has seen a steady increase in FDI inflows, interrupted for the first time in the first financial quarter of 2019.

Under the India's regulatory regime, FDI can only be made into equity shares, fully and compulsorily convertible preference shares ("CCPS") and fully and compulsorily convertible debentures ("CCD") and subject to fulfilment of certain conditions, partly paid shares and warrants.

Full article

FDI in India: A bird’s eye view

Introduction

In the first ever budget speech since the adoption of the Constitution of India, the then Finance Minister John Mathai said, "foreign capital is necessary in this country, not merely for the purpose of supplementing our own resources, but for the purpose of instilling a spirit of confidence among our investors" (1). Although Mathai's views did not inform or shape India's foreign investment policies at least for the next four decades, India has finally adopted a welcoming attitude to foreign investment. But, has India adopted a fully liberalised investment regime? Not yet. India has been welcoming and at the same time wary of foreign investment.

The evolution of FDI norms and regulations in India has been a roller-coaster journey. As a newly independent post-colonial nation, India in its initial years regarded inflow of capital with deep suspicion. In 1948, the Industrial Policy Statement (IPS), presented during the debates of India's Constitutional Assembly, projected a hostile approach to foreign investment, and noted that a law should be implemented to 'scrutinise every single foreign investment project before giving approval and that, as a rule, the major interest in ownership and effective control should always be with Indians.' (2) On the contrary, following the 1950-51 budget, the Nehruvian government cautiously welcomed foreign investment, going as far as to promise reduction of discrimination between Indian and foreign owned companies (3). In India's third five-year plan, while the focus was on self-reliance in the domestic industry, foreign investment was nevertheless permitted in select sectors. (4)

The Nehruvian years were followed by a period of extensive nationalisation and restrictions on foreign investment under his daughter, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Aside from nationalising the banking and insurance sector, the Indira Gandhi government enacted the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1973 that required government approval and licensing for nearly all entrepreneurial activities. The period came to be known as 'license-permit raj'.

The 1990s, however, saw a shift after away from inward looking economic policies and towards liberalisation of the economy. India opened up foreign investment in a number of sectors, participated in the Uruguay round of trade negotiations that led to the formation of the World Trade Organisation. On the domestic front replaced the restrictive and draconian Foreign Exchange Regulation Act 1973 (which required prior approval of the government for nearly all forms of investment) with a more liberal act governing foreign investment namely the Foreign Exchange Management Act 1999. The early 2000s saw India adjusting to globalisation and a liberalised economy.

In the past decade, promoting foreign investment in a manner that sustains domestic industry has been at the forefront of India's economic policy. For over six fiscal years, India has seen a steady increase in FDI inflows, which was interrupted for the first time in May 2019 when the Government recorded a 1% decline in FDI inflows. (5)

Having provided a sketch of India's history in dealing with foreign direct investment, this article examines India's FDI policy and provides an overview of the regulatory regime governing FDI, the policy concerns shaping FDI inflow into India and India's relationship with international investment agreements and bilateral investment treaties.

The Regulatory Landscape

FDI in India is regulated under the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (FEMA) which was enacted to replace the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1974. The Foreign Exchange Management (Transfer or Issue of Security by a Person Resident Outside India) Regulations, 2017 more commonly known as the FEMA 20R Regulation, sets out the specific rules and compliances applicable to FDI in India. The FEMA 20R defines foreign direct investment as 'investment through capital instruments by a person resident outside India in an unlisted Indian company; or in 10 percent or more of the post issue paid-up equity capital on a fully diluted basis of a listed Indian company' (6) . FDI under the FEMA20R is permitted in most sectors, with some sectors requiring prior approval of the government. The FEMA20R sets out the permitted routes of investment, the kinds of capital instruments that may be held by foreign investors and the various regulatory compliances to be fulfilled by foreign investors in India. A brief overview of the key features of the regulatory regime on FDI, specifically covering the instruments under which FDI is permitted and the key compliances under the rules is set out in Annex 1 of this Article.

The compliances to be fulfilled by foreign investors and Indian investee companies is under the purview of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (the DPIIT) is responsible for formulating the FDI Policy in India, setting out the sectors in which FDI is permitted and the limit upto which foreign investment is permitted in such sector. The regulatory oversight for FDI in India, specifically the compliances to be fulfilled by foreign investors and Indian investee companies is under the purview of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

The FDI Policy

As of 2019, the only sectors where FDI is completely prohibited in India are: (a) Lottery Business including Government / private lottery, online lotteries etc, (b) Gambling and betting including casinos, (c) Chit Funds (7) , (d) Nidhi Company (8), (e) trading in Transferable Development Rights, (f) Real Estate (not being development of town shops, construction of residential / commercial premises, roads or bridges and registered Real Estate Investment Trusts) or Construction of farm houses, (g) Manufacturing of cigars, cheroots, cigarillos and cigarettes, of tobacco or of tobacco substitutes, and (h) sectors not open to private sector investment i.e. atomic energy, railway operations, space, defence etc. (9)

Apart from these sectors, FDI is permitted in most other sectors in India through doone of the three 'entry routes' – (i) Automatic i.e. no prior government approval is required, (ii) Government Approval i.e. prior approval of the relevant Ministry of the Central government is required and (iii) Government + Automatic i.e. no approval is required up to a certain percentage of investment, but upon crossing that threshold, prior government approval is required. The FDI Policy is regularly updated from time to time by the DPITT and any sectoral conditions to FDI are notified thereunder.

In the past five years, the banking, financial, insurance, technology, outsourcing and research and development sectors have attracted the maximum FDI (in terms of dollar value) (10). In 2019, telecommunications, services and Computer Software sectors have thus far attracted the most amount of FDI inflow, with Singapore being the largest source of FDI inflows to India. (11)

In general, thus, Indian domestic policy towards foreign investment has seen many reforms in the past two decades and is actively geared towards the promotion and encouragement of FDI inflows into India. The incumbent government of India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has extensively advocated for 'simplifying FDI rules and ensuring that at a time when FDI is shrinking all over the world, it is growing in India'. (12)

Ease of Doing Business

In 2019, as a result of a number of regulatory and administrative reforms, India's rank in the Ease of Doing Business Index issued by the World Bank improved by 14 positions. India is currently ranked as the 63rd among 190 nations (13). While this rise in ranking was a significant improvement, there are still certain areas identified by the report where India lags, such as – enforcement of contracts (163rd), registration of property (154th) and payment of taxes (115th). According to the report, the average time taken for the registration of a property is 58 days and the cost, on an average, is approximately 7.8% of the property's value. This is more time consuming and expensive than many other high-income countries. Another area of concern is the resolution of commercial disputes. The Ease of Doing Business report estimates that it takes approximately 1,445 days for a company to be able to resolve a commercial dispute at a court of first instance. This number is reportedly three times the average in an OECD country. (14)

The average time taken for the registration of a property is 58 days and the cost, on an average, is approximately 7.8% of the property's value

Keys Issues in FDI Regulation

Regulating investment in the financial services sector is a point of note for the Indian Government. India is currently a net importer of financial services, running a small trade deficit of USD 373 million as of 2017-2018. However, due to concerns around round tripping, regulations governing 'overseas direct investment' from India to foreign countries and related FDI into India, has been heavily regulated. FDI into India from companies, which have received some investment from an Indian company, is prohibited even if it may be for bona fide purposes. (15)

While the FDI policy has been progressively liberalised, issues such as sponsoring of visas for foreign workers in India, insuring of assets situated in India by foreign insurers etc continue to be restricted. (16)

Despite these limitations, the Central Government of India continues to take a pro-active approach to liberalising the FDI policy and ease out regulatory restrictions on FDI. This approach however is in stark contrast to India's approach to Bilateral Investment Treaties.

Bilateral Investment Treaties

Signed between countries hoping to foster foreign investment between themselves, BITs are treaties that provide certain protections to investors of one party of a BIT vis-à-vis its investment in the party. BITs provide protection to investments by 'imposing conditions on the regulatory behaviour of host state and thus preventing undue interference with the rights of the host state.' (17)

Globally, the last three decades have been marked by an impressive growth of international investments and trade along with the integration and openness of international markets. These developments have led to intense competition among countries, particularly developing countries, to generate more FDI inflows in order to boost their domestic rates of investment and accelerate economic development (18). The first BIT was signed between Germany and Pakistan in 1959; post the loss of all foreign investment in Germany after the Second World War. By 1990, there were over a 100 BITs in force, and as of 2019, various agencies and organisations count the number of BITs in force to be in excess of 2000. This is a staggering number despite the fact that many BITs have been terminated post 2012.

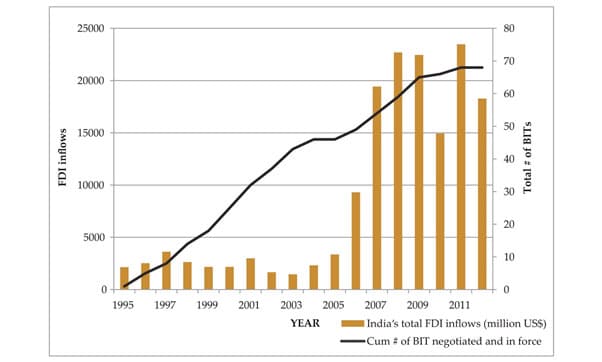

India has been actively negotiating BITs since its economic liberalization to intensify cross-border flows of investment. It had only one BIT (in force) in 1995, but as of 2015, there were nearly 89 BITs in force in India (19). According to current data maintained by the UNCTAD, India has terminated nearly 67 of the BITs and only 14 continue to remain in force as on date (20). This mass termination of BITs in the last four years is a direct result of the number of Investor-State Disputes filed against India. (21)

Before examining India's recent stand in BITs and its reluctance to agree to investor state dispute settlement mechanisms, it is crucial to examine the relationship between the signing of BITs and increase in inflow of FDI. The Indian government holds the view that increase in the number of BITs has no direct bearing on increasing FDI inflows (22). A brief overview of the literature analysing the linkages between BITs and inflow of FDI is provided below.

BITs and inflows of FDI – Linkages

There exist conflicting views in studies undertaken by various bodies on the nature of association between BITs and FDI flows. While some studies estimated a positive correlation between BITs and FDI flows, others do not arrive at similar results (23). A study, which analysed bilateral FDI flows from 20 OECD countries into 31 developing countries, found that BITs did not seem to directly or otherwise result in or even attract additional foreign investment (24). Similar findings were corroborated by another study in 2003, which noted that BITs appeared to have limited impact on a country's, particularly a developing country's ability to attract FDI (25). A study that collected data on the impact of total number of BITs signed, on FDI inflows in 15 developing countries (specifically in South and Southeast Asia) found that BITs had a higher impact on the FDI inflows of developed countries than it did on the FDI inflows of developing economies. (26)

On the contrary, a 2010 study claims that there 'appears to be an interaction between the conclusion of BITs on the one hand, and level of political risk and property rights on the other hand' (27). This study notes that countries that appeared to be "risky" investee countries from the perspective of political risk and stability and the protection of property rights are likelier to attract more foreign investment by entering into BITs or trade agreements with investment chapters. (28)

A study more specifically focused on India shows that there is at least correlation, if not causation, between the number of BITs signed by India and the FDI inflow in USD (29). The figure below is a representation of the findings of the study.

Figure: 1 Trends in India's BITs Negotiated (and in Force) and Total FDI Inflows (1995–2011)

Source: Bhasin N. and Manocha R. (2016)

Regardless of the economic effect, it is undeniable that there has been a backlash against the investor state dispute settlement process (ISDS) and BITs in general around the world (30). Questions have been raised on the role of BITs in limiting the policy space available to host governments to address issues of public concern (31). The reaction to BITs by termination is not limited to India. South, Bolivia, Australia, Ecuador and Venezuela are among countries, which have either terminated BITs, or rejected the ISDS procedure or altogether denounced the ICSID Convention.

India's reluctance to accept BITs and more specifically the ISDS mechanism enshrined in BITs can be traced back to the arbitration claims filed against it under its BITs.

India and Investor-State Dispute Settlement

ISDS, when provided for under a BIT, allows an investor to directly issue a claim of arbitration against a host state for any breach of the investment protections granted under the BIT. Such protections typically include protection against unlawful expropriation, fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security of the investment etc.

ISDS, when provided for under a BIT, allows an investor to directly issue a claim of arbitration against a host state for any breach of the investment protections granted under the BIT

The FDI Policy is regularly updated from time to time by the DPITT and any sectoral conditions to FDI are notified thereunder

One of the approaches that many scholars take while examining India's stand on BITs and foreign investment, is to split India's outlook towards BITs into two phases - Pre-White Industries Dispute phase and the Post-White Industries Dispute Phase. White Industries v India (32) is a landmark ISDS arbitration against India, which was decided in favour of the investor.

Pre-White Industries Dispute Phase

One of the earliest arbitration claims made against India under a BIT was by Dabhol Power Company (DPC), which was set up as a joint venture by the Enron Corporation, Bechtel Enterprises and General Electrical Corporation (33). DPC had entered into an exclusivity contract with the electricity board of the Indian state of Maharashtra – the Maharashtra State Electricity Board (MSEB), a public sector enterprise. According to the contract, the MSEB was the exclusive purchaser of power generated by DPC. Upon a default of this contract by MSEB (the reasons provided were alleged irregularity by DPC and political opposition, among other things) (34), General Electrical Corporation and Bechtel Enterprises invoked arbitration against India through its Mauritius subsidiaries under the India-Mauritius BIT. This case did not result in an arbitral award as it was settled between the parties; however, it did mark the first set of major ISDS claims against India. (35)

White Industries v India

White Industries Australia Limited is an Australian mining company, which engaged on a long-term contractual basis with Coal India Limited, an Indian state-owned enterprise in 1989. A commercial arbitration dispute arose between the two parties due to various reasons and a tribunal of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) rendered an award in favour of White Industries. While White Industries filed in one Indian High Court (High Court of New Delhi) to enforce the award, Coal India Limited applied to another Indian High Court (the High Court of Kolkata) to set aside the award. The dispute was subsequently escalated before the Supreme Court of India and it remained pending on appeal for over 9 years. White Industries, because of the delay before the court, invoked ISDS proceedings under the India-Australia BIT. The tribunal, in a landmark decision, ruled in favour of White Industries based on a legal protection enshrined in the India-Korea BIT and which was invoked under the India – Australia BIT by way of the 'Most Favoured Nation' clause. The tribunal awarded White Industries a compensation of USD 4.08 million.

The Post-White Industries era

Subsequent to the White Industries v India award, and likely as a result of it, a number of foreign multinational corporations served ISDS notices to India on a range of regulatory measures which India had implemented. These regulatory measures included 'imposition of retrospective taxes' (issued by Vodafone corporation under the India-Netherlands BIT), revocation of telecom licenses (issued by the Tenoch Holdings under both the India-Russia BIT and the India-Cyprus BIT) and cancellation of spectrum licenses (issued by German company Deutsche Telecom under the India-Germany BIT, and by Devas Mauritius Limited under the India-Mauritius BIT). (36) According to the ISDS Database of UNCTAD, there are currently 12 pending ISDS claims against India, another 9 which have been settled, 1 that has been discontinued and 2 where an award has been made (one in favour of the Investor i.e. White Industries v India, and one in favour of India i.e. LDA v India). (37)

As a result of this series of ISDS claims against India, the government undertook a review of India's policy towards BITs with a view to overhaul the existing system. The review process began in 2012 under a Central Government Working Group and was intended to balance investor rights against the Indian Government's obligations towards public interest and policy. (38) While 2016 Model BIT does retain the ISDS mechanism, it imposes a number of conditions and pre-requisites, which need to be met by Investors prior to invoking such measures. (39)

Indian Backlash against BITs

As noted previously, like many other developing countries, India has reacted to ISDS claims by making a departure from the existing BIT regime. India has adopted a two-pronged approach with respect to its existing BITs. First, the government has already served notices of termination to countries (inter alia, United Kingdom, France, Germany and Sweden) with whom existing BITs have either expired or are scheduled to expire. India proposes to renegotiate a new BIT with these countries based on India's 2016 Model BIT. For a number of other countries (inter alia, China, Finland, Bangladesh and Mexico), India had requested for joint interpretive statements (JIS) to be made to clarify ambiguities in the text of BITs which may result in an expansive interpretation by ISDS Tribunals. Furthermore, the new Model BIT is the basis on which any new BITs or Investment Chapters in Free Trade Agreements will be entered into by India.

Thus, on the one hand, the Indian Government continues to liberalise and bring about reforms in its corporate sector and its FDI Policy, on the other hand it remains reluctant to international treaty commitments guaranteeing protections for foreign investments.

Annex I

Key Features of Regulations governing FDI in India.

The section below provides an overview to the key regulatory features of investing in India. It captures only FDI i.e. foreign direct investment and does not include other forms of investment such as investment through debt instruments, investment in listed securities i.e. foreign portfolio investment, investment through investment through investment vehicles such as FVCIs.

Permitted Equity Instruments

Under the India's regulatory regime, FDI can only be made into equity shares, fully and compulsorily convertible preference shares ("CCPS") and fully and compulsorily convertible debentures ("CCD") and subject to fulfilment of certain conditions, partly paid shares and warrants.

| Equity | CCPS | CCD | |

| Description | Stake in equity of company, involves participation and responsibility in governance of the company, returns are based on risk. | Instrument is mandatorily convertible into equity. Dividends are pre-prescribed. Some role in governance may be contractually agreed to. | Debenture instrument which is mandatorily convertible into equity. Assured interest / coupon on instrument until conversion into equity. |

| Returns | Dividends, which may be declared out of the profits of the Company. Dividend is not capped. | Dividends, which may be declared out of the profits of the Company. Dividend is not capped. | Fixed or variable interest / coupon is pre-determined. Coupon is not dependent on profits. Coupon rate not capped but typically benchmarked at market interest or dividend rates. |

| Statutory Liquidation Preference | Equity is ranked last in the liquidation waterfall. | Ranks higher than Equity shares but lower than CCDs. | Ranks higher than CCPS in the liquidation waterfall. |

Reporting requirements

At the time of investing in India, and subsequently thereafter, a foreign investor (and the Indian investee company) is required to fulfil certain reporting requirements under the FEMA 20R. These forms are submitted to the RBI and are facilitated by 'authorised dealer' banks identified by the RBI.

| SI. NO. | Form of reporting Requirement | Description of Form | Timeline for filing |

| 1 | Annual Return on Foreign Liabilities and Assets (FLA Return) | FLA Return is required to be submitted mandatorily by all the India resident companies which have received FDI any of the previous year(s), including current year. | on or before 15 July every year. |

| 4 | Single Master Form {w.e.f. 30.06.2018} | Integrates the reporting requirements for FDI in india, irrespective of the instrument through which foreign investment is made. Subsumes of FC-GPR*, FC-TRS**, and reporting forms for investment into LLPs, and investments through convertible notes. |

1. FDI reporting in Form FC-GPR under SMF has to be done within 30 days after the allotment. 2. Reporting under FC-TRS under SMF has to be done within 60 days of transfer of capital instruments or receipt / remittance of funds whichever is earlier. |

| 5 | Advance Reporting Form (ARF) | Form to report the details of the amount of received by Indian company which is receiving investment from outside India for issue of shares or other eligible securities under the FDI Scheme. | Not later than 30 days from the date of receipt in the Advance Reporting Form (ARF) |

| 6 | *Form FC-GPR is filed by an Indian company for issue of shares to a foreign investor (and includes investment received indirectly by way of merger / amalgamation into another Indian company). Physical filing of the form has been discontinued and the form is subsumed within the Single Master form. | ||

| 7 | **Form FC-TRS is filed in the case of foreign investment done by way of a transfer of shares from an Indian resident holding the shares to a foreign investor or vice-versa. (In contrast to investment via a fresh issue of shares. Physical filing of the form has been discontinued and the form is subsumed within the Single Master form. | ||

Conclusion

India's consolidated FDI policy and progressive amendments to the FEMA20R Regulation have resulted in a steady liberalisation of the norms governing foreign investment in India. However, the FDI inflows to India have not matched up to the reforms undertaken in this area. As recent as in September 2019, India diluted FDI restrictions across sectors such as single-brand retail trading, commercial coal mining and contract manufacturing (40). Taxation reforms such as the implementation of the uniform Goods and Services Tax (GST) (41) and reduction in corporate taxes and corporate reforms such as the implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, amendments to the FEMA20R etc., have been announced in the past five years. Data released by DPIIT indicates that India recorded an FDI inflow of approximately USD 16.3 billion in the first quarter of 2019. While the impact of these measures in the long run on FDI inflows remains to be seen, the Government has positioned these reforms as key reforms targeted at increasing FDI inflows into the country.

At the same time, India has been very cautious in multilateral and bilateral engagements on investor and investment protections. India has resisted participation in the negotiations on investment facilitation at the WTO (42) and has terminated most of its Bilateral Investment Treaties (almost 70 BITs). India's approach to foreign investment continues to reflect the outlook presented by Minister Mathai in 1951 – welcome and yet cautious.

Laws

- Foreign Exchange Regulation Act 1973 available at (FERA)

- Foreign Exchange Management Act 1999 available at

- (6) Regulation 2(xviii), Foreign Exchange Management (Transfer or Issue of Security by a Person Resident Outside India) Regulations, 2017, FEMA 20(R)/2017-RB,available at

- Foreign Exchange Management (Transfer or Issue of Security by a Person Resident Outside India) Regulations, 2017 (Amended up to March 08, 2019) available at

- Manas Chatterji and B. M. Jain.Conflict and peace in South Asia. Emerald Jai available at

- Aseema Sinha.The regional roots of developmental politics in India. Indiana University Press. available at

- Anne O. Krueger.Economic Policy Reformas and the Indian Economy. The University of Chigado Press available at

- Sujit Choudhry, Madhav Khosla and Pratap Bhanumehta. The Indian Constitution. Oxford University Press available at

- Express Economic history series- 3:How ‘draconian’ FERA clause triggered flush of retail investors. The Indian Express.

- P.V. Raghavan, R. Vaithianthan and V.S. Muriali.General Economics for the CA Common Porficiency Test(CPT). Pearson available at

- Ranjan p., NationalContestation of International Investment Law and International Rule of Law inRule of Law at National and International Levels: Contestations and Deference, Hard Publishing, April 2016, at pg 115-142 available at

- Ranjan P, Barring Select Sectors, Nehru was not Opposed to Foreign Investment, The Wire, 27 May 2018, available at

- (1) Budget Speech, 1950-51 Budget, available at

- (2) Industrial Policy Statement of 1948, Constituent Assembly of India(Legislative) Debates, Vol III, No. 1, pp. 2385-86

- (5) Press Trust of India, FDI inflows record first decline in six years this Fiscal, Hindu Business Line,May 2019, available at

- (7) Industrial Policy Statement of 1948, Constituent Assembly of India(Legislative) Debates, Vol III, No. 1, pp. 2385-86

- (9) Official government of India website on India’s FDI policy, available at

- (10) Punj S, The Shop’s open but no one’s shopping, India Today, 30 August 2019, available at

- (11) FDI up 28 percent in April – June 2019,Hindu Business Line, 05 September 2019, available at

- (12) Partnering India a Golden Opportunity says PM Modi, The Economic Times, 26 September 2019, available at

- (13) World Bank, Doing Business: India Report 2020, available at

- (14) Sharma Y. S, India Jumps to 63rd position in World Bank’s ease of doing business 2020report, 24 Oct 2019, available at

- (15) Report of the High Level Advisory Group, 12 September 2019, available at

- (16) Cyril Amarchand.Mangaldas Foreign investment issues for project companies in India. August2019 available at

- (17) Dolzer R and Schruer C,Principles of International Investment Law, (2nd Ed.), Oxford University Press, Nov 2012, at p13

- (18) Bhasin, N, Foreign direct investment in India: Policies, conditions and procedures¸ New Century Publications, 2012

- (19) UNCTAD Investment Policy Hub, Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator: India, (Hereinafter ‘UNCTAD Database: India’) available at

- (21) Ranjan P., India and Bilateral Investment Treaties: Refusal, Acceptance, Backlash, Oxford University Press, 2019, at Pg 277.

- (22) Ibid at Pg 273 citing, Government of India Ministry of Commerce, International Investment Agreements between India and other countries, 2011.

- (23) Bhasin, N., & Manocha, R., Do Bilateral Investment Treaties Promote FDI Inflows? Evidence from India, Vikalpa, 41(4), 275–287 (Hereinafter ‘Bhasin N. and Manocha R. (2016)’)

- (24) Hallward-Driemeier, M., Do bilateral investment treaties attract FDI? Only a bit and they could bite, World Bank Policy Research Paper No. WPS 3121, 2003

- (25) Tobin, J., & Rose-Ackerman, S., Foreign direct investment and the business environment in developing countries: The impact of bilateral investment treaties, William Davidson Institute Working Paper No. 587, 2003

- (26) Banga, R., Impact of government policies and investment agreements on FDI inflows, Working Paper No. 116, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, November 2013 as cited inBhasin N. and Manocha R. (2016)

- (27) Mina, W., Do bilateral investment treaties encourage FDI in the GCC countries? African Review of Economics and Finance, 2010, Vol. 2(1), 1–29

- (30) Waiber M., Kaushal A., Liz Chung K., Balchin C.,The Backlash Against Investment Arbitration: Perceptions and Reality,The Peter A. Allard Schoolf of Law: Allard Research Commons, 2010 at pg 5., available at

- (31) Garcia-Bolivar O. E., Sovereignty vs. Investment Protection: Back to Calvo?, 24 ICSID Review, 2009, Foreign Inv. L. J. 470-47;

- (32) White Industries Australia Ltd v India, Final award, IIC 529 (2011), 30th November 2011, Arbitration available at

- (33) Nishith Desai & Associates, Bilateral Investment Treaty Arbitration and India, 2018, available at

- (34) Bechtel and GE Mount Investment Treaty Claim Against India, ISDS Platform, 2003, available at

- (35-37) UNCTAD Database: India, available at

- (36) Ranjan P., Singh H. V., James K., Singh R., India’sModel Bilateral Investment Treaty – Is India Too Risk Averse?, Brookings India Impact Series, August 2018 at Pg 9, available at

- (38) Government of India, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion, Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 1290(July 25, 2016) available at

- (39) The Model BITis available at

- (40) Press Trust of India, Governmentokays 100% FDI in Contract Manufacturing, eases rules for Single Brand Retail,Business Standard, August 2018, available at

- (41) Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017 available at

- (42) Balino S. And Bernasconi-Osterwalder N, InvestmentFacilitation at the WTO: An attempt to bring a controversial issue into an organisation in crisis, Investment Treaty News, International Institute for Sustainable Development, June 2019, available at

Comments

Related links

Main menu